Innovation

1976

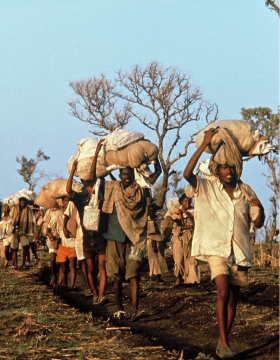

In 1979, an estimated 600,000 Cambodian refugees sought safety in different camps on the Thai border. MSF worked with a team of about 100 volunteers on injury management activities (surgery and rehabilitation) and nutrition and obstetrics programs. (Photo credit: ©️MSF)

CAMBODIAN REFUGEE CRISIS

In 1976, MSF established its first large-scale medical programme during a refugee crisis, providing medical care for waves of Cambodians seeking sanctuary. At that age, the idea of "humanitarian aid" was still relatively new. MSF teams in Thailand had no experience in refugee settings and no guidelines.

Challenge: Management of drugs and supply

Dealing with large number of refugees in Thailand was a new challenge to MSF, a rather young organization at that time. The field teams consisted of just doctors and nurses, with a high turnover, most of whom had no experience with the tropical diseases they had to learn how to treat.

Jacques Pinel, a pharmacist, joining the MSF project in Thailand in 1979 and described MSF as an "organization without organization."One example was that drugs from different donor countries were in boxes piled under a tarpaulin and field workers took whatever medicines were easiest to find.

Innovation: Develop pre-packed emergency kits for various situations

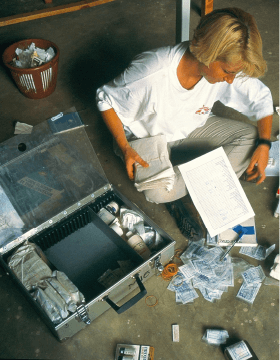

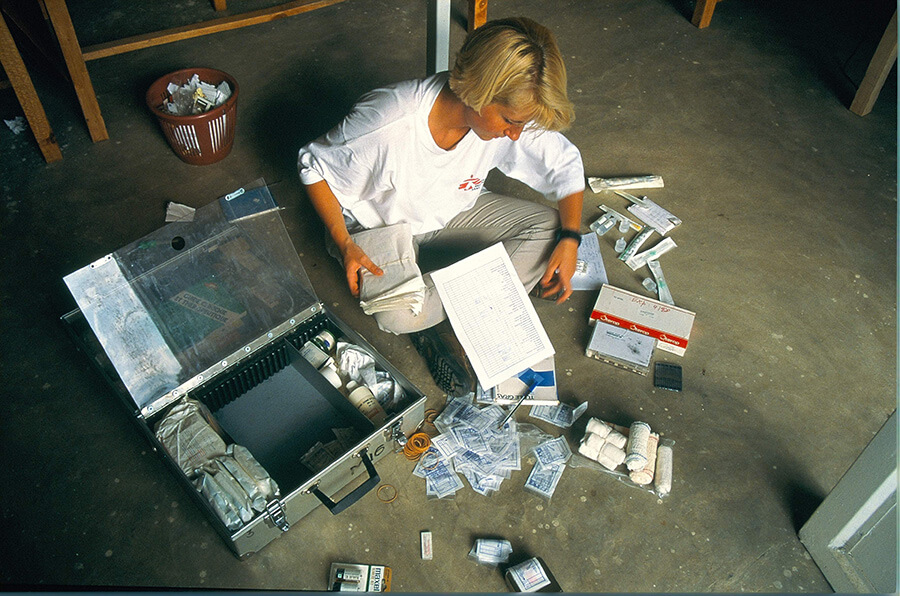

Based on the work in Thailand, MSF learnt another lesson which is still valid today - the need to develop emergency kits that are adapted to each specific situation. Jacques Pinel created the first emergency kit in a kind of wooden cabinet, with all drugs and medical supplies perfectly displayed in what looked like little drawers. However, when he had finished the work, he and the team realised that the wood used to build it was far too heavy and could only be carried in the back of a pick-up truck. Hence the nickname, "semi-mobile equipment."

In the refugee camps MSF served, there were women ready to give birth, patients who had injuries, respiratory infections, and malaria that needed care. Several standard toolkits, including the "semi-mobile equipment", were made.

They were large boxes made by local carpenters that could serve as an examination table and that contained emergency kits and drawers in which supplies were classified by need. Standardized drug and equipment lists, including user manuals, were packed into kits.

A nurse checking the content of an emergency kit. (Photo credit: ©️Herve de Ribaucourt)

Since then, MSF Logistics has created many others. The vaccination kits for measles, meningitis, and yellow fever enable MSF quickly to set up a cold chain and they include all medical and logistic supplies necessary for a vaccination campaign by several teams of vaccinators. There is also a kit for creating a hospital with inflatable tents within 48 hours, which has been used to treat patients in the aftermath of natural disasters in countries like Haiti, Philippines and Nepal, and in conflict zones of Yemen and Syria.

.jpg)

1976

The MSF hospital in Agok is the only facility providing secondary care in the entire Abyei region of South Sudan. This structure deals with emergencies, surgeries, treatments of HIV, tuberculosis, chronic diseases as well as neglected diseases, such as snake bites, a real scourge in the region. In 2019, in order to improve the quality of care, a radiology room was set up and the pharmacy was extended. A lack of specialized structures in the surrounding states forces some patients to travel very long distances to get to Agok hospital, some have to walk for up to 10 hours. This phenomenon illustrates the need for a comprehensive hospital in a country where health care is almost non-existent. (Photo credit: ©️Laurence Hoenig/MSF)

DECENTRALISED CARE - HIV TREATMENT

Significant advances having been made in HIV treatment over the last 25-30 years, including the efficacy and affordability of anti-retroviral therapy. Though the cost of first-line drugs is now cheaper than ever, but more than 12.6 million people were still missing out on receiving treatment at the end of 2019. While 1.7 million people became newly infected with the virus in 2019. Amongst 38 million people living with HIV/AIDS, over two-thirds of them live in sub-Saharan Africa.

Challenges: Huge needs but very few resources to manage a chronic disease in poor countries

The reality of the HIV pandemic is that the largest public health effort that humanity has ever undertaken to manage a chronic disease is fought primarily in poor countries. There are huge needs but very few resources in these countries. They cannot cope with a continuous flow of patients who require life-long follow up and treatment.

Stable paitents want to live a normal life, without having to frequently come to overcrowded hospitals and queue for hours just to pick up their medication. In most circumstances, the time on the journey and in the hospital means they will lose a day's pay, which means lost food for themselves and their family.

In long running conflict areas like South Sudan and the Central African Republic, people will face a deadly cocktail of obstacles to access medical facilities for their treatment. Many people living with HIV have to make long and often dangerous journeys to find a clinic that offers HIV testing and care. Those who reach them, sometimes find empty shelves instead of the much-needed drugs, making it impossible for them to continue their ARV treatment.

Adaptation: Decentralise treatment with patient at the centre of care

Over the years, MSF has piloted and developed ways of decentralising treatment with a patient-centered and community-focused approach. The most successful models of care for people living with HIV are those

The decentralised care separates different kinds of appointments. Since the needs of different patients are different : there are those to see a doctor or nurse for a check-up, which is only necessary once a year for patients whose HIV treatment is monitored by viral load count. And there is picking up a supply of daily ARV drugs, which can be as frequent as once every month. The delivery of drugs is organised at community level through the support of peer groups.

A patient-centered approach could mean:

- Adapting clinic opening hours to suit the patients. They might be early morning clinics, so people can drop by on their way to work or late-night clinics for commercial sex workers;

- Letting people have three or even six-month supplies of their daily ARV drugs, instead of the usual one-month supply.

.jpg)

A doctor consults a patient in Michael Mapongwane Community Health Centre's HIV/TB unit in Khayelitsha, Western Cape, where MSF works alongside the health ministry to provide a range of integrated HIV TB services. (Photo credit: ©️Oliver Petrie)

Taking the town of Khayelitsha, South Africa as an example, MSF piloted the adherence clubs model. Under this approach, patients, led by a lay worker, gather once every two months at the health facility or at a community venue, for ARV distribution. The group allows for peer support and health education among its members. Patients visit the health facility once a year for a clinical consultation and a viral load test. The model is being further expanded within the community, and adherence clubs are being organised in patient's homes instead of at a health centre. This model is well adapted to urban environments, especially where time spent at the clinic is an issue for patients.

Today, even in the resource limited areas, or conflict affected areas, a person who tests positive for HIV is offered counselling and started on treatment immediately.

.jpg)

1980s

Nduta refugee camp, Tanzania, 6 August 2017 – The busy maternity unit of the MSF hospital. (Photo credit ©️ Erwan Rogard)

CLINICAL GUIDELINES

The most familiar problem has been and still is finding the resources MSF needed to practice medicine in places where everything was limited. This was particularly in refugee camps and remote areas, where everything had to be built from scratch.

Challenge: Large numbers of patients and a high turnover of medical personnel

MSF was and is often faced with large numbers of patients from poor communities facing significant physical threats. This was combined with a high turnover of medical personnel, most of whom had no experience with the tropical diseases they now had to learn how to treat.

The usual medical hierarchies would not necessarily be reproduced in the field. Because practical experience in these regions was the main qualification for the success of these missions, young physicians could exercise responsibilities that would normally be performed by department heads in their own countries, and nurses could take over the medical management of a mission. They needed as much help as possible from a text that was adapted to these emergency conditions.

So the MSF clinical guidelines were born out of the organization's mission to provide the best medical care it can during crises and their aim was to streamline the management of issues in the field and to standardize medical practices.

Adaptation: Develop scientific evidence based medical guidelines to standardise medical practices

In the early 1980s, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) drafted an emergency medical guide in Thailand. Oxfam designed a nutritional kit. MSF teams revised the texts based on their own experience to anticipate responses to a range of situations in which it would be used. This became the Clinical Guidelines.

The Clinical Guidelines were called the "green guide," after the color of its cover. It was expanded and revised by its users.

Later, a guide to essential drugs was added to the green guide. It was designed for doctors unfamiliar with tropical environments, for nurses, and for national doctors working with MSF.

The introduction to the current edition explains:

MSF has been producing medical guidelines based on scientific evidence and lessons from our work in the field. The guidelines are the collaborative work of a number of experienced medical practitioners and specialists, and were developed for non-specialised medical staff. Data sources include the World Health Organization (WHO) and other internationally recognised medical institutions, as well as medical and scientific journals.

The guides are designed for use by medical professionals involved in curative care at the dispensary and primary hospital. At the outset, the guides met the need for streamlining operations management, but they also sought to standardize medical practices. They take into account what may be basic technical environments in terms of diagnostic equipment, as well as restricted therapeutic means. They can be used as a basis for medical staff training.

Inside Magaria hospital's paediatric unit. Early in the morning, MSF paediatrician Julia Rappenecker accompanied by the centre's medical personnel check on the children who have been admitted to the intensive care unit in the last 24 hours. (Photo credit ©️Erwan Rogard)

.jpg)

Adapting to the digital era

In 2017, MSF launched the Medical Guidelines mobile app for iOS and Android, together with a website. The app functions as a locally stored mobile reference, which is available offline. It contains all the contents of the MSF Clinical Guidelines and Essential Drugs manuals, and contact information for all MSF offices around the world. In addition, the app can be accessed at any time on a variety of mobile devices, and has the ability to be updated instantaneously.