Speaking Out

1984

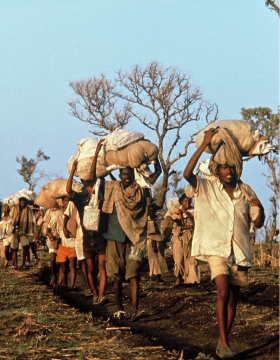

Tigray. Exodus. Drought and famine are raging in this region, and the fighting of the Tigray People's Liberation Front has provoked violent attacks from the Ethiopian government forces. (Photo credit ©️ Gamma)

ETHIOPIA FAMINE

In Ethiopia, the 1984 famine is still referred to as one of the worst humanitarian disasters in history. The United Nations estimates it caused nearly 1 million deaths, with millions more displaced and left destitute, unable to rebuild their lives. Along with many other organisations from around the world, MSF worked to bring aid and relief to those in need.

But how did this famine happen in the first place?

In 1960, members of the security and military forces attempted a coup d'état against the Emperor. It failed but social and economic problems emerged, and the monarchy became embroiled in conflicts in Eritrea and with Somalia. By the early 1970s, one-third of Ethiopia's soldiers were in Eritrea, while the rest remained in the country, putting down rebellions. In January 1974, there began a series of mutinies led by junior officers and senior non-commissioned officers.

By 1980, the situation was made worse by drought, leading to poor harvests in the north. The drought intensified yearly, peaking in 1984, and putting one-sixth of the population at risk of starvation. By March of 1984, the Ethiopian government appealed internationally for food aid. Despite efforts, by October of the same year, 8 million were at risk of starvation.

Challenge: One of the worst humanitarian crises in history

News footage shocked the world into action. Because it was so difficult to distribute food across large areas with poor roads, starving populations left their farms and began to congregate in places where they hoped to find food.

Despite all of this, the government delayed officially acknowledging the famine's existence. Media coverage of the catastrophe made it possible to raise an unprecedented amount of international aid from governments and individuals in the West. However, the government diverted a portion of that aid to carry out forced population transfers from rebel areas in the northern plateaus to the more fertile plains in the south of the country, where the population could be more easily controlled. The famine prompted the rural population to head to distribution centres, where they were loaded onto trucks, often requisitioned from aid organisations, and transported like livestock. This further hampered delivery of aid to the south. Conditions en route were appalling, and no preparations were made to resettle the families when they arrived in the malaria-infested regions. At least 100,000 people were estimated to have died in 1985 during resettlement operations.

Tigray. Health centre in Axum. Drought and famine are raging in this region, and the fighting of the Tigray People's Liberation Front has provoked violent attacks from the Ethiopian government forces. (Photo credit ©️MSF )

Adaptation: Denouncing the political famine

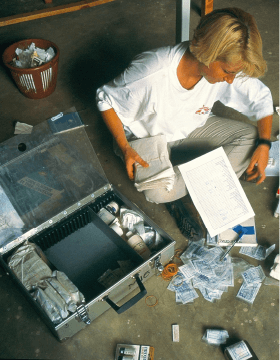

From April 1984, French section of MSF opened medical programmes in the northern Wollo region, near the Korem distribution centre. Programmes in Kobo (September 1984), Kelala and Sekota (June 1985) followed. The authorities pressed for transfers to the south, regularly impeding the teams' work. On several occasions, the teams were forbidden to treat certain individuals or to distribute blankets. MSF teams also witnessed round-ups carried out by the Ethiopian army among the camp populations.

On several occasions, the authorities refused to authorise MSF requests to open a therapeutic feeding centre in Kelala, which could have prevented the deaths of several thousands of children. In October 1985, the French section of MSF publicly denounced the government's refusal to open a therapeutic feeding centre, along with its misuse of international aid for forced population transfers, and the shocking conditions under which transfers were being carried out. In the days that followed, the Ethiopian government expelled the French section of MSF from the country.

Dr. Rony Brauman, President of MSF France from 1982 to 1994, doing medical consultation. (Photo credit ©️Sebastiao Salgado)

In 1986, following its expulsion, MSF in France conducted a campaign in Europe and the United States to explain its actions, which received considerable media coverage. The Ethiopian authorities suspended the transfer operations temporarily.

Meanwhile the teams from MSF Belgium had been working in Idaga Hamus in the Tigre since March 1985 and in Zambalessa since the summer of 1985. Team members did not witness forced transfers, and so did not take a public position. They continued to develop their programmes with the agreement of Ethiopian authorities. Similarly, the Dutch section of MSF, created in September 1984, which was working with Ethiopian refugees in Somalia, did not take a public position either.

.jpg)

1999

The moment protesters take over the stage during the official opening ceremony of the 50th Union Conference on Lung Health on 30th October 2019. (Photo credit: ©️Sophia Apostolia/MSF)

ACCESS CAMPAIGN

When your work involves lifesaving medical action, what do you do when the medicine your patients need is unavailable, expensive or toxic? While MSF is focused on humanitarian medical aid, the Access Campaign makes sure the right medicine is available to the patients who need it most.

Challenge: Scale of the problem

In the 1990s, treatment for HIV/AIDS included new, effective drugs called antiretrovirals. But in developing countries, pharmaceutical companies charged high prices for antiretrovirals, keeping them out of reach of most people living with the virus. The number of AIDS deaths in these countries kept rising. Many of them were places where MSF worked.

When patients and healthcare advocates worked together and generated political pressure, the price of HIV medicines dropped dramatically, allowing millions to receive life-saving treatment.

The same problem exists with other diseases that persist in many places where MSF treats patients, from tuberculosis and sleeping sickness, to malaria, drug-resistant infections and patients do not have access to vaccines.

Adaptation: A solution that is an ongoing campaign

The Access Campaign was started in 1999 and it works to help people from to get the treatment they need to stay alive and healthy. This goes beyond life-saving drugs and includes tests and vaccines that are available, affordable, suited to the patients' needs, and adapted to the places where they live.

The vital missing link is to align drug development more closely with patient needs. What's necessary are medical tools that are more affordable, innovative, and effective in the places where we work.

In 1999, MSF was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. With the proceeds, the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) was established. DNDi is a collaborative, patient-centred, non-profit organisation. DNDi is proving that change and creative thinking in medical research and development can be an effective catalyst for new approaches to patient-centred drug development and access.

Since its inception, DNDi has already delivered seven new treatments for malaria, sleeping sickness, Chagas disease and paediatric HIV/TB coinfection, among other diseases.

Tuberculosis treatment and trials

One of the diseases that Access Campaign has worked hard to treat is tuberculosis (TB). In 2019, TB remains as the world's deadliest infectious disease.

However, many people are unable to get tested, and the ones who do get diagnosed are often unable to get or complete the treatment they need. Cost is a significant factor, but so are the toxic side effects.

In 2012, the oral drug bedaquiline came to market. It was developed by pharmaceutical corporation Johnson & Johnson (J&J). WHO recommended bedaquiline as the backbone of DR-TB treatment, to replace older, more toxic drugs. But it has cost too much for most patients.

For many years, Access Campaign pressured J&J to lower the price. Finally, in 2020, J&J announced a reduced price of US$1.50 per day.

.jpg)

Activists from MSF protested at the door of the company Johnson & Johnson, West Zone, Brazil, for the reduction in the price of bedaquiline, a drug against tuberculosis (TB). In a performance act, the company representatives withdrew money from patients and deposited it in a medicine box-shaped safe. (Photo credit: ©️Julia Chequer/MSF)

But lower prices are just one part of the solution. Shorter, more effective treatment regimens are another.

In 2017, MSF, in partnership with many other health research organizations, pioneered new a clinical trial aiming to find a radically improved course of treatment for DR-TB. In January 2017, TB-PRACTECAL was born.

In March 2021, TB-PRACTECAL stopped enrolling patients. Its independent data safety and monitoring board indicated that the regimen being studied was superior to current care, and more patient data was extremely unlikely to change the trial's outcome.

Vaccine inequality in the pandemic

In 2020, everything changed when COVID-19 took over the world.

One year and over 150 million cases later, the world sees some hope, as vaccines are approved for use and vaccinations are taking place across populations. But as with many other diseases, access to vaccines, testing and treatment varies greatly in each country.

Over many months, the Access Campaign has asked governments to prepare to suspend and override patents and take other measures, to ensure availability and reduce prices to save more lives; and to work in solidarity to meet not only their domestic needs but also to support other countries to get access to effective medicines, diagnostics, and vaccines.

In October 2020, at the World Trade Organization (WTO), India and South Africa put forward the landmark ‘TRIPS waiver' proposal. As of April 2021, the proposal is officially backed by 59 sponsoring governments, with around 100 countries supporting overall.

With COVID-19, as with many other diseases, the work of the Access Campaign continues.

A banner deployed by MSF in front of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Geneva calling on certain governments to stop blocking the waiver proposal on intellectual property (IP) during the pandemic. (Photo credit: ©️Pierre-Yves Bernard/MSF)

.jpg)

.jpg)

2005

An interior view of the MSF Trauma Centre, 14 October 2015 after a sustained attack on the facility in Kunduz, northern Afghanistan. (Photo credit: ©️Victor J. Blue)

ATTACKS ON HEALTH FACILITIES

In war-torn countries such as Syria, Yemen, South Sudan and many others, health facilities have been attacked, looted and destroyed. Attacks against medical facilities and health workers, deprive people of health services, often when they need them the most.

Challenge: Staff killed in attacks at medical facilities

Since 2005, MSF has lost 23 staff in nine separate events, including during the storming or bombing of hospitals. There have been more than 350 incidents involving MSF health facilities, ambulances, and the communities we serve in Afghanistan, South Sudan and other countries.

Adaptation: MSF advocacy response and UN Resolution 2286

UN Security Council (UNSC) passed the Resolution 2286 in May 2016.

MSF worked hard to ensure that the provision of medical care on both sides of the front line is protected. The resolution was an attempt to reassert the legitimacy and protected status of humanitarian medical action.

The resolution also enhanced the protection of healthcare in conflict. It formally extended protection under International Humanitarian Law (IHL) to humanitarian and medical personnel exclusively engaged in medical duties. This includes staff, medical activities and facilities of private humanitarian organisations, such as MSF. It also clarified and solidified the protection of hospitals.

.jpg)

United Nations Security Council, September 2016. MSF International President, Dr Joanne Liu, addresses a special session of the Council on 28 September 2016. Dr Liu demanded that the UNSC permanent members implement the resolution they passed in May, #2286, for the protection of civilians and healthcare in conflict zones. (Photo credit: ©️Paulo Filgueiras)

The problem remains

Five years since UN Resolution 2286 was passed, hospitals and medical and humanitarian workers continue to be threatened and targeted in conflict.

In 2020, there were eight reports of incidents in MSF projects. In Afghanistan, armed groups brutally attacked the MSF maternity wing in Dasht-e-Barchi hospital. In Syria, hospitals and clinics we support have been routinely bombed. Ambulances in war-torn Yemen often come under attack. Armed incursions into our health facilities have occurred in places including Sudan. This year, MSF has recorded six incidents already in just the first quarter.

MSF still demands answers

With the COVID-19 pandemic still raging, attacks on healthcare continue. We continue to employ mechanisms, such as ensuring we're clearly identified and that groups know who and where we are. In places like Yemen and Afghanistan, our logo is very clearly marked on our ambulances and on the roof of our hospitals, and we proactively share the coordinates of our medical structures. These negotiations and mechanisms require constant maintenance and vigilance through dialogue with parties to the conflict.

It's crucial for us and the work we do that we preserve the sanctity and protection of medical care, and that we have access to all parties in a conflict to secure that protection. Establishing these ‘deconfliction' arrangements – which then must be respected by all sides – is vital to prevent attacks.

But we cannot do it alone. States must take all the necessary steps to ensure the maximum protection for the wounded and the sick, and medical and humanitarian personnel.

MSF logistics coordinator Nabil Bahar (left) and a daily worker identifying the roof of MSF Hospital in Taiz with a big MSF logo banner, so the hospital is not hit by airstrikes. MSF opened the Mother and Child hospital in Al-Houban area in Taiz in November 2015. (Photo credit: ©️Pierre-Yves Bernard/MSF)

.jpg)

In the wake of an attack where the army or a state armed group was involved, an independent and impartial fact-finding investigation can often be an effective way to bring accountability and help put in place measures to avoid it happening again.

Three years after the 2016 bombing of the MSF-supported Shiara Hospital in northern Yemen, the UK and US-supported Joint Incidents Assessment Team – which was appointed by the Saudi and Emirati-led Coalition engaged in Yemen – failed to provide any true accountability.

Following incidents like these, MSF conducts our own internal review and assessment of the event, often making our own findings public. But sometimes – regardless of whether the circumstances were clear or not – we decide it's simply too dangerous for our patients, our staff, or both, to continue working where there has been an attack. On a number of occasions, this has led to the extremely difficult and heart-breaking decision to withdraw – the consequences of which often means people are left without adequate access to healthcare.

.jpg)

1994

On April 6, 1994, on the plane back to Kigali, the Burundian and Rwandan presidents were killed. The next day, the massacres began and the entire country sank into violence: political assassinations, pogroms against Tutsis, open conflict between the RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front), part of the army and the presidential guard. The fighting caused massive displacement of populations to Zaire (now called Democratic Republic of Congo), Tanzania, Burundi and within Rwanda itself. MSF is taking care of these displacements in Gitarama and Gikongoro. (Photo credit ©️ MSF)

RWANDA GENOCIDE

For many years, there had been tensions between the Hutu and the Tutsi peoples of Rwanda. Though the Hutu settled in the country many centuries ago, the Tutsi minority ruled from the 16th century until the arrival of the Europeans in the 19th century.

In 1961, Rwanda declared itself a republic, and an all-Hutu provisional government came to power. Thousands of Tutsi began fleeing Rwanda.

Then from 1987, a predominantly Tutsi rebel organisation had been leading a war of re-conquest. In 1990, they first invaded Rwanda from the north, then a ceasefire was negotiated in early 1991, and negotiations between them and the government began in 1992.

On 6 April 1994, the plane carrying the Rwandan President was shot down as it approached the capital, Kigali. The slaughter — primarily of the Tutsi minority — commenced in the days that followed.

From April to July 1994, between 500,000 and one million Rwandan Tutsi were systematically exterminated by organized Hutu militiamen. The genocide was the outcome of long-standing plans by Hutu extremists. The extremists also killed many Rwandan Hutu who opposed the massacres and they seized power in Kigali in early July.

Challenge: Challenges beyond medical

From the moment these forces took control, MSF teams witnessed abuses and brutalities committed by the administration and the armed forces, particularly against displaced populations and detainees crammed into prisons. The violence increased in the months that followed, and rumours about the brutal behaviour of the new regime were corroborated by reports produced by human rights organisations.

When MSF teams attempted to help their neighbours in nearby houses, militiamen threatened them and ordered Tutsis to hand themselves in. In one such incident in Murambi, a town about 20 kilometres from Kigali, militiamen armed with clubs and machetes murdered a man right in front of several MSF volunteers.

On 13 April 1994, Dr. Jean-Hervé Bradol, the MSF programme manager for Rwanda and Burundi, arrived in Kigali with his emergency team to open a surgical programme and treat survivors.

"On 14 April, Rwandan Red Cross colleagues saw militia fighters take wounded patients out of ambulances and kill them on the side of the road."

Bradol had what seemed to be an impossible task in such circumstances: to triage the wounded. "I examined each wounded patient and tried to determine whether it was worth the risk of travelling through part of the city and crossing all the militias' barricades. We treated less serious wounds on site, knowing that medical care was less critical to those patients than avoiding militia fighters who were planning to kill them."

Bradol estimates at least 200 Rwandan colleagues were killed during the genocide. "We don't know the exact number. Our offices were looted and our personnel lists were destroyed so it was impossible to get a precise count."

.jpg)

Consultation of a child in Rwanda by an MSF medical worker. (Photo credit ©️Severine Blanchet)

Adaptation: Speak out to criticise the inhuman condition

In April 1995, an MSF team witnessed the Rwandan army's deliberate massacre of over 4,000 displaced people in the Kibeho camp in southwest Rwanda. MSF spoke out publicly to denounce the killing and produced a report based on the eyewitness accounts of its volunteers. The report documented the extent of the massacre, and differed greatly from the dismissive account prepared by an international commission of enquiry into what had occurred.

MSF again spoke out publicly in July 1995, to criticise the inhuman conditions in which detainees in Gitarama prison were being held and to call for improvements. This stance was backed by medical data collected by MSF volunteers.

Distribution of medicines in Gikongoro. (Photo credit ©️MSF)

.jpg)

In December 1995, the French section of MSF was expelled from Rwanda. The whole MSF movement regarded this move as a settling of scores by the Rwandan Government, given that it was volunteers of the French section that had directly witnessed events at Kibeho and had initiated the public denunciations.

At the end of 2007, MSF ended its 25 years activities in the country. The work had included assistance to displaced persons, war surgery, programmes for unaccompanied children and street children, responding to epidemics and so on.