Logistics

1997

Nurse Hawa Lamboi writes notes on the chart of Rugiatu, who is six months pregnant and suffering from cholera, at Mabela Cholera Treatment Center in Mabela quarter, Freetown, Sierra Leone. (Photo credit: ©️Holly Pickett)

CHOLERA OUTBREAK IN ZAIRE (NOW DRC)

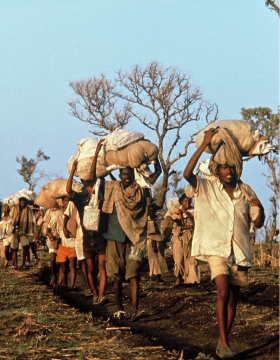

In July 1994, hundreds of thousands of Hutu refugees began fleeing Rwanda following the genocide and conflict. Humanitarian operations were launched, including by MSF teams who were present in countries bordering Rwanda, including DRC (then called Zaire), to assist the refugees.

In Apr of 1997, a large cholera outbreak occurred among 90,000 Rwanda refugees living in three temporary camps between Kisangani and Ubundu in Zaire.

Cholera is an acute diarrheal infection caused by ingestion of food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholera, or through contact with faecal matter or vomit from infected people. A cholera infection is often mild or without symptoms but can sometimes be severe, causing profuse watery diarrhea, vomiting and leg cramps. The patient rapidly losses body fluids, leading to dehydration and shock. Without treatment, patients can die within hours.

Cholera is a highly treatable disease and most people will recover with prompt administration of Oral Rehydration Salt (ORS). Without treatment though the prognosis of severe cholera is poor and mortality rate can reach 50%. With adequate care however, it is typically 1% or less.

Challenge: A deadly but treatable disease

The keys to cholera outbreak control are hand hygiene, isolation, faeces management and clean water supply, which are all really hard to get right and deliver in places with very limited resources. Other challenges of this outbreak include:

- Most cholera patients were severely malnourished and suffered from concurrent health problems, e.g. malaria or acute respiratory illnesses

- Majority of deaths occurred at night when MSF health care workers were absent because the camps were too dangerous to stay in overnight

- Cholera also occurred among health care workers in the cholera treatment center (CTC), which highlighted the importance of cutting the transmission line of the disease

- The refugees were often moved around by unidentified armed groups, which interrupted cholera-control measures

Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) Health Promoter, Faida Kanyombe, during a health promotion session about Cholera for the population of a small village along the River Congo. June 2 2016. (Photo credit: ©️HBorja Ruiz Rodriguez/MSF)

Adaptation: Cholera Treatment Centre to control the disease

In response to the 1997 outbreak, active case identification and referral was started by hiring Rwandan community health workers familiar with the refugees in their parts of the camp. Cholera-control measures included filtration and chlorination of the camps' water systems, health education, and construction and maintenance of latrines. MSF established two referral medical centers and a CTC in the camps.

A CTC is a specialized isolation ward designed to prevent the spread of cholera. It provides medical care to a large number of patients while isolating them from hospital structures where disease may spread. Typically it has its own general services (latrines, showers, kitchen, laundry, morgue and waste area), stocks and resources (medical and logistics, water and electricity) and it operates 24 hours a day. Over the years, the design of the CTC refined by MSF has made a significant contribution to the cholera epidemic response globally.

Key components of a CTC are: disinfection points, clean water source, latrines, waste management, hydration, recovery zone, supplies and administration.

In 2018, MSF published a clinical guideline for doctors, nurses, lab technicians, medical auxiliaries, WATSAN specialists and logisticians on the ‘Management of a Cholera Epidemic'.

MSF Staff administrate an oral vaccine to a boy at the Nyaragusu refugee camp. MSF is carrying out an oral cholera vaccination campaign in Nyaragusu refugee camp in Tanzania for 56,000 Burundian refugees. A cholera outbreak began among the refugees in mid-May. As at 22 June, some 3,086 cases and 34 deaths have been reported in Tanzania. (Photo credit: ©️Erwan Rogard/MSF)

Interactive website on MSF's CTC: http://ctc.msf.org/layout/en

.jpg)

2005

Pakistan, Mansehra, 2005. Global view on MSF's inflatable hospital tents that have been installed in front of the district hospital. (Photo credit: ©️Rémi Vallet)

PAKISTAN EARTHQUAKE

On Saturday 8 October 2005, an earthquake measuring 7.6 on the Richter scale, one of the biggest in recent years in this region, hit Pakistan, North India and Afghanistan. More than 150 aftershocks added yet more landslides. By December, over 73,000 were estimated to be killed, 128,000 injured and over 2.8 million displaced in Pakistan.

Challenge: A large number of injured people in mountainous area inaccessible to health services

The mountainous terrain in that part of Pakistan means that some areas were all but inaccessible, making delivery of aid and even assessment of the needs difficult. The situation was made worse by roads blocked by landslides. We had to set up assistance in remote areas that are accessible essentially only by helicopter, or walked to get to our patients in remote locations where road access was blocked. MSF provided care to a large number of seriously injured people, and see to the material needs of those affected.

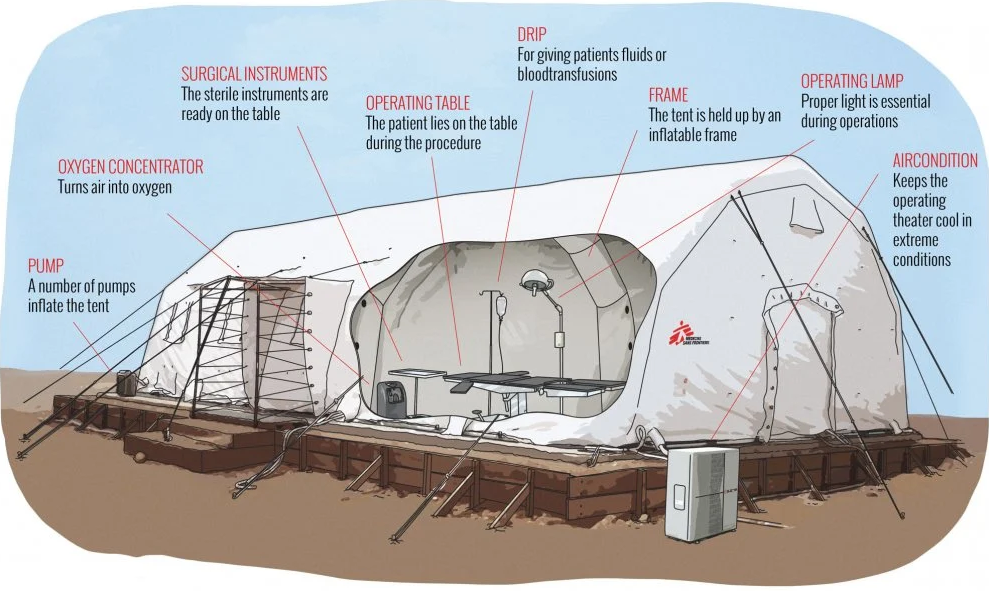

MSF deployed a surgical team and one of the inflatable hospitals to Mansehra, Pakistan, to help improve the quality of care there. The temporary hospital measured over 1000 m² with a 120-bed capacity, built under nine inflatable tents. This structure, which included four operating suites, an emergency room, and an intensive care unit, was put up in two weeks. This was the first time MSF was able to establish a substantial surgical presence following an earthquake. Around 700 injured received care in this temporary hospital in Pakistan.

Too often after a man-made or natural disaster, essential health structures including hospitals are completely destroyed. While some injuries can be treated in open air or temporary clinics that MSF often put up in these circumstances, significant numbers of patients will require surgery that can only be effectively performed in a closed and sterile environment.

Construction or even refurbishment of damaged health structures with operating theatres that meet the stringent medical requirements take far too long.

.jpg)

12 days after the earthquake, badly injured survivors are still found in great numbers by medical teams on the ground or rescue helicopters. Several are being evacuated from a remote village where a mobile MSF Holland medical team gave them the first medical treatment. (Photo credit: ©️Bruno Stevens)

Adaptation: Inflatable field hospital to provide surgery and post-operative treatment

In 2004, when MSF teams saw the Italian Army using inflatable tents during the response to the tsunami in Southeast Asia, we immediately recognized their potential for us. We adapted the design, and began equipping our teams with state-of-the-art inflatable field hospitals—dramatically reducing the time it takes to begin providing trauma surgery and post-operative treatment.

MSF developed a 120-bed inflatable field hospital with a self-contained heating, sanitation, and water-purification system. This hospital can be quickly deployed around the world.

Advantages:

- Fast to install – 24-48 hours from delivery to receiving first patients

- Easy to disinfect

- Delivered as a kit. Surgical equipment and other materials already included to start initial service.

- Adaptable- can be set up as operating theatres, in-patient wards, pharmacy.

- Reusable (can be packed and re-deployed in another location)

Challenges:

- A lot of manpower is needed for the initial placement and set-up

- Temperature control is a challenge in hot climates

MSF's Inflatable Hospital Increases Medical Aid in Pakistan: